How Much Does NCAA Tournament Seeding Really Matter?

March 13, 2015 - by Jordan Sperber

Note: This research was originally conducted in 2014 by Jordan Sperber, and the post was updated for 2015 by TeamRankings.

Selection Sunday always sparks a raging debate among college basketball fans about which four teams deserve a 1 seed from the NCAA Selection Committee.

When it comes to filling out your NCAA bracket, though, the more important question is this:

How much does getting a 1 seed — and seeding in general — actually matter when it comes to NCAA tournament performance?

It’s something our algorithmic models will consider closely as they identify the best bracket pool picks for 2015, and it warrants an objective study.

(Here’s how we build smarter brackets, by the way.)

The No. 1 seed landscape in 2015

As the major conference tournaments get into swing, six teams are battling it out to land a top seed in the 2015 NCAA tournament, according to our 2015 bracketology projections: Kentucky, Villanova, Arizona, Wisconsin, Duke, and Virginia. A couple other teams, Gonzaga and Kansas, are extreme long shots.

1 seeds historically perform very well in the NCAA tournament, so there is understandably a lot of media and fan focus on — or rather, obsession with — that seed line. After all, 1 seeds are (in theory) the four best teams in the country and have (in theory) the four easiest roads to the Final Four.

Still, NCAA tournament 2 seeds share a fairly similar story. So is all this obsession over landing a 1 seed justifiable based on past tournament history? And more generally, just how important is seeding overall?

Is seeding or team strength a better predictor of NCAA tournament success?

As a research project, I compiled a large set of historical data about NCAA tournament teams.

One of the many statistics I collected was a pre-tournament adjusted efficiency rating for every team, courtesy of Ken Pomeroy. The rating is an effective way to measure team strength heading into the NCAA tournament, so I used both adjusted efficiency and other stats from TeamRankings for my analysis.

As a basic first step, I looked at the correlation between NCAA tournament seeds and NCAA tournament wins, and between pre-tournament adjusted efficiency and tournament wins.

Since the 2004 NCAA tournament, the r-squared value between seeding and wins, excluding play-in games, is .36. That means that if you only knew were the seeds of NCAA tournament teams, but no other stats about them (win-loss record, strength of schedule, offensive or defensive efficiency, average margin of victory, etc.) then you would be able to explain roughly 36% of NCAA tournament wins in this data sample.

On the other hand, pre-tournament adjusted efficiency and NCAA tournament wins have an r-squared value of .32, which implies that seeding could actually play a larger role than team strength in explaining tournament success.

In other words, a team that lucks out and gets a better seed than they should have, based on what their advanced stats say about their performance level, may be better off in the tournament than a statistically superior team that ends up being seeded lower by the Selection Committee.

Does the NCAA Selection Committee really do better at projecting a team’s tournament success than advanced stats do? Stat geek biases aside, that conclusion seems hard to believe. Instead, this is probably some preliminary evidence supporting the importance of seeding.

Do the best teams get the best seeds in the NCAA bracket?

A key point about the seeding process is that the NCAA tournament selection committee largely looks at descriptive information (e.g. team “resumes” largely focused on wins and losses) as opposed to predictive information (e.g. efficiency differential stats).

As a result, cases can arise like the Florida Gators in 2013. The Gators received a 3 seed that year, implying that they were no better than the 9th best team in the nation, despite leading the entire NCAA Division I in pre-tournament efficiency.

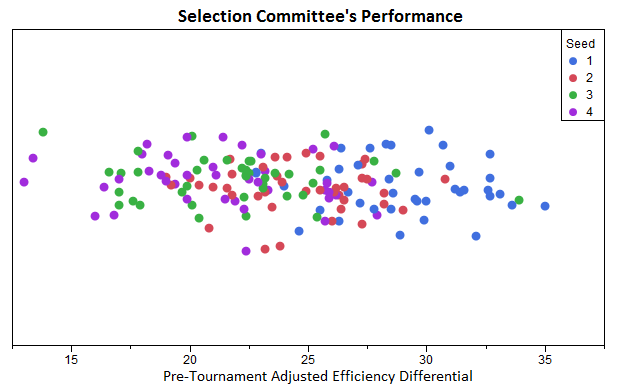

As it turns out, cases like 2013 Florida are actually an exception relative to the last 10 years. Take a look at the graph below, which looks through the 2013 season:

2012 Ohio State and 2013 Florida are the only two teams with a pre-tournament efficiency differential of over 30 not to get a 1 seed in the NCAA bracket. In general, the Committee’s choices of 1 seeds over the years have lined up well with predictive metrics.

Another thing to note is that the gap in efficiency between 3 seeds and 4 seeds has not been nearly as big as the gap between 1 seeds and 2 seeds.

This shouldn’t come as a huge surprise, since most years there are a couple dominant teams that separate themselves from the rest of the country. It’s much easier to distinguish the few dominant teams from the next best tier than it is to differentiate a good 3 seed from a usually-not-that-much-worse 4 seed.

How are NCAA tournament teams of similar strength affected by their seed number?

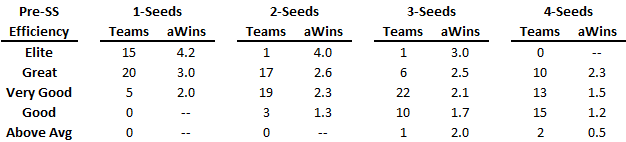

To draw some better conclusions about seeding, we have to account for team strength. I grouped every 1 seed through 4 seed in the last 10 years into five categories based on efficiency differential: elite, great, very good, good, and above average. This allows us to look at how, for example, statistically “great” teams have performed across various seeding levels.

First, though, a big caveat: Sample size is still a significant issue with this approach, even with 10 years worth of data to look at. The NCAA tournament is famous for its variability, and we are only working with 40 teams at each seed number.

Still, we can look for any striking differences, and for patterns that are consistent across bins:

Notice how “great” and “very good” are the only two classifications with at least five teams at each seed line. In both cases, with the exception of the very small sample of only five “very good” 1 seeds, there is a consistently downward sloping trend of NCAA tournament wins as seed number gets worse.

For example, the 20 “great” 1 seeds, according to advanced stats, have won an average of 3.0 NCAA tournament games, but the 10 “great” 4 seeds have won only 2.3 games on average.

Compare this to the trends going down each column. “Elite” 1-seeds have won 4.2 games per tournament, while “very good” 1-seeds have won only 2 games per tourney. Sample sizes in some bins are small, but in every case where there are more than a few teams, the expected pattern is present: Worse teams win fewer games in the tournament.

What does it mean for your bracket picks in 2015?

It seems clear that both seeding and team strength matter, which is a logical conclusion, but at least we’ve now got some data to support it.

Still, for the best teams in the land at least, team quality (based on advanced stats) seems more important. For 1 through 4 seeds over a 10-year period, the difference in tournament wins changes more drastically when you hold seed number constant and look at varying levels of team quality, than when you hold team quality constant and look across varying seed numbers.

Put another way, if a great team according to the stat geeks gets a bit of a snub by the Selection Committee in terms of seeding, there’s no clear evidence here that their implied “harder road to the championship” should make a big negative impact on your assessment of their chances.

In conclusion, the bracket is designed to give the 1 seeds the easiest roads, but seeding isn’t everything. When it comes to maximizing your odds to win your 2015 NCAA bracket pool, you need to be smarter than the NCAA Selection Committee.

But don’t forget one last thing…

One final note deserves mentioning, though. It’s critical to remember that every NCAA tournament is different. In any particular tournament, a great team with a great seed can still face a very tough path to the championship, given the dynamics of their region, and other factors like their travel schedule.

So never, ever take any bracket advice that’s based on “golden rules” or seed number-based trends. But that’s a topic for our 5 Signs Of Terrible Bracket Picking Advice post.

Printed from TeamRankings.com - © 2005-2024 Team Rankings, LLC. All Rights Reserved.